Chapter 0: Re-examining null — Unraveling the Philosophy of "Absence" Through Algebraic Structures and the History of Type Systems

1. Posing the Problem: Why Do We Need to Represent “Absence”?

Section titled “1. Posing the Problem: Why Do We Need to Represent “Absence”?”Programming, in essence, is the act of modeling aspects of the real world or abstract systems. And in virtually any system we model, we inevitably encounter situations where a value might be missing, a state might be considered “empty,” or an operation might not yield a result. How we represent this concept of “absence” is a ubiquitous and critically important requirement for building correct and robust software.

Consider these common, concrete examples:

-

The Empty Spreadsheet Cell: A cell in a spreadsheet grid naturally embodies this concept. A cell can hold a definite value (a number, text, a formula), or it can be simply empty. This empty state is not an error; it’s a fundamental part of the spreadsheet model, signifying the absence of data in that location.

-

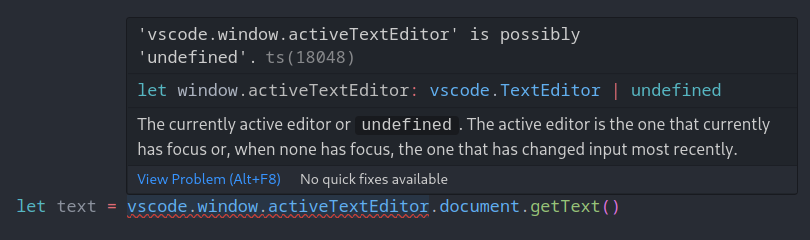

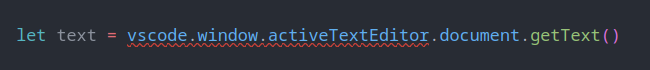

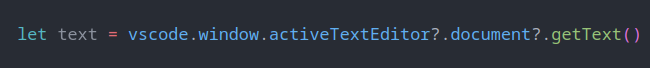

No Active Text Editor: In a modern IDE like Visual Studio Code, a user might have several files open in tabs, or they might have closed all of them. The state where there is no currently active or focused text editor is a perfectly valid and expected state within the application’s lifecycle.

These examples illustrate that “absence,” “emptiness,” or “nullity” is not merely an exceptional circumstance or an error. It is often a real, necessary, and legitimate state within the domain we are modeling. Therefore, how our programming languages and type systems allow us to represent and interact with this state is of foundational importance.

2. The Theoretical Pillar: From Function Pipelines to Algebraic Structures (A Revisit)

Section titled “2. The Theoretical Pillar: From Function Pipelines to Algebraic Structures (A Revisit)”Before diving into the core of the “absence” debate, we must return to the theoretical pillar of this book. This is the deliberate, logical flow, established in Unit 2, of how the definition of an “algebraic structure” is naturally derived from the idea of a “function pipeline.”

First, our starting point is the fundamental concept in functional programming: the “pipeline,” where data flows through a series of functions.

-

Components of a Pipeline:

- Every pipeline operates on data of a specific Type.

- Functions transform this data in well-defined ways.

- This naturally leads us to work with

(Type, Function)pairs.

-

Binary Operators are Functions:

- Next, we adopt the perspective that common binary operators, like

1 + 2, are also a kind of function. For example, the+operator can be seen as a function with the type(int, int) -> int.

- Next, we adopt the perspective that common binary operators, like

-

The Correspondence of Types and Sets:

- A Type in programming corresponds deeply to a Set in mathematics. The

inttype is the set of all integers, thebooltype is the set{true, false}, and thestringtype is the set of all possible strings.

- A Type in programming corresponds deeply to a Set in mathematics. The

Integrating these insights reveals a clear correspondence before us.

| The World of Programming (Pipeline) | The World of Mathematics (Structure) |

|---|---|

| Type | Set |

| Function | Operation |

The (Type, Function) pair we were handling in our pipelines was, conceptually, the exact same thing as the (Set, Operation) pair known in the world of mathematics as an algebraic structure.

In conclusion, an algebraic structure is not some esoteric mathematical topic. It is a design pattern extremely familiar to us as programmers: **“a combination of a data type (a Set) and a series of operations (Functions) that preserve the structure on that data type.”

All subsequent arguments in this chapter are built upon this simple yet powerful principle.

3. The Mathematical Identity of null: It is the “Empty Set”

Section titled “3. The Mathematical Identity of null: It is the “Empty Set””The concept of “absence” is not merely an invention for the convenience of software development; it has deep roots in mathematics. The notion often represented by null in programming finds a direct and powerful correspondence in a fundamental structure, specifically within Set Theory.

- The Empty Set: In axiomatic set theory, the empty set (denoted ∅ or {}) is uniquely defined as the set containing no elements. It is a cornerstone of the theory, allowing for the construction of all other sets and mathematical objects. The concept of

nullcan be seen as directly analogous to this empty set—representing the absence of any value within a given type (where a type is viewed as a set of its possible values).

This connection is profound. It suggests that null, far from being merely a problematic value, actually corresponds to a well-defined, indispensable concept in mathematics. Our perspective in this book is that types are objects in the Category of Sets (Set), and functions are the morphisms between them.

4. The Truth Behind the “Billion-Dollar Mistake”

Section titled “4. The Truth Behind the “Billion-Dollar Mistake””Despite its conceptual and mathematical legitimacy, the null reference, particularly as implemented in many early object-oriented and imperative languages, gained notoriety for causing frequent and often hard-to-debug runtime errors: the dreaded NullPointerException in Java, NullReferenceException in C#, and segmentation faults in C/C++.

Sir Tony Hoare, a pioneer in programming language design, famously lamented his introduction of the null reference in ALGOL W around 1965, calling it his “billion-dollar mistake”:

I call it my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965… This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years.

This powerful narrative took hold, leading to a widespread conviction that the very concept of null itself was inherently flawed and dangerous.

However, we must now conduct a critical re-evaluation, returning to our principle that “an algebraic structure is a pair of (Set, Operation).”

Was the real mistake the fundamental concept of representing absence (null, analogous to the Empty Set)? Or was it the utter lack of an adequate language mechanism to manage this concept without catastrophic runtime failures—that is, the lack of a robust type system to distinguish nullable from non-nullable references, and the lack of safe operators for handling potentially null values?

This book strongly argues for the latter. The “billion-dollar mistake” was not the existence of null itself, but the failure to define the “safe operations” that should be executed when null is received. From the perspective of algebraic structures, it was the failure to design the algebraic structure that should have been paired with null (the Empty Set). That is the truth of the matter.

5. Option Types as a Historical Consequence

Section titled “5. Option Types as a Historical Consequence”In the face of the dangers posed by unchecked null references, the functional programming community, particularly languages rooted in the Hindley-Milner (HM) type system (such as ML, Haskell, and early F#), championed a different solution: eliminating pervasive null references from the language core and representing optionality explicitly within the type system using Option types (often called Maybe in Haskell).

The Option<T> type is typically defined as an algebraic data type (ADT)—a sum type—with two cases:

-

Some T: Indicates the presence of a value of typeT. -

None: Indicates the absence of a value.

The primary advantage of this approach is compile-time safety enforced by the type system. Because Option<T> is a distinct type from T, a programmer cannot accidentally use an Option<T> value as if it were definitely a T. The type system mandates explicitly handling both the Some and None cases, usually through pattern matching, thereby preventing null reference errors at compile time.

However, while solving the null pointer problem within the HM framework, the Option type approach introduces its own set of consequences and critical perspectives:

-

Critique 1 (Structural Complexity): While

Option<T>elegantly handles a single level of optionality, nesting them (Option<Option<T>>) can lead to structures that feel more complex than the simple presence/absence they represent. -

Critique 2 (Philosophical/Historical Legitimacy): Was the complete elimination of a

null-like concept truly the most theoretically sound path, or was it an overreaction based on the “Null is evil” myth? -

Critique 3 (HM Design Philosophy and Constraints): The prevalence of

Optionin HM-based languages is also deeply intertwined with the technical characteristics and limitations of the HM type system itself.

Note: Technical & Historical Deep Dive – HM Systems, Null, Option, and Union Types

The historical trajectory of Hindley-Milner (HM) based languages strongly favoring Option/Maybe types over implicit null was deeply rooted in HM’s core design goals (soundness and type inference) and its algorithmic machinery (unification, affinity for Algebraic Data Types).

Standard HM presents significant theoretical and practical hurdles to integrating untagged union types like T | null or subtyping natively. HM’s algorithm works by “unifying” type variables with concrete types. A type like T | null, where null is implicitly a subtype of all reference types, complicates this simple unification algorithm and risks compromising soundness.

On the other hand, Algebraic Data Types (ADTs) like Option<T>, with their explicitly tagged constructors Some(T) and None, are a very natural fit for HM’s pattern matching and unification algorithms. The compiler can clearly identify the type as Option<T> and force the programmer to handle both cases.

In short, Option/Maybe was the most natural path for HM’s design goals and algorithmic constraints. Directly integrating T | null union/subtyping posed a significant theoretical and practical challenge for HM. This difficulty is specific to HM’s formulation; it does not mean that handling “absence” in a sound type system without Option is theoretically impossible—just that it was not the path HM chose.

It is possible that this constraint of HM inadvertently reinforced the “Null is evil” narrative and discouraged the exploration of alternative, sound approaches that retain a null-like concept.

6. Another Path: The “Safe null” Proven by TypeScript

Section titled “6. Another Path: The “Safe null” Proven by TypeScript”While HM-based languages adopted Option types, a different path has been successfully demonstrated by languages like TypeScript. This prompts us to reconsider the narrative that null itself is an unmanageable “billion-dollar mistake.”

TypeScript, by integrating null and undefined into its type system as Nullable Union Types (e.g., string | null) and providing mechanisms like type guards (e.g., if (value !== null)) and optional chaining (?.), has achieved a high degree of practical null safety. Programmers can work with potentially absent values, and the compiler, through sophisticated control flow analysis, helps prevent many common null reference errors at compile time.

function processText(text: string | null): void { if (text !== null) { // Within this block, TypeScript knows 'text' is a 'string' console.log(`Length: ${text.length}`); } else { console.log("No text provided."); }}

This success of TypeScript raises an important question: if nullability can be managed this effectively with appropriate type system features, why did the HM tradition so strongly favor the Option type? Was the problem truly null itself, or was it the specific limitations of classic HM type inference? It is clear that Option is not the only solution.

7. The Timeline Library’s Philosophy: Theoretical Legitimacy and Practical Simplicity

Section titled “7. The Timeline Library’s Philosophy: Theoretical Legitimacy and Practical Simplicity”Based on the foregoing analysis—the fundamental nature of null (the Empty Set), the historical context and potential drawbacks of the Option approach, and the practical success demonstrated by TypeScript—this Timeline library adopts a specific, deliberate philosophy for handling absence:

We embrace null as the primary representation for the absence of a value and combine it with a strict discipline for safe handling.

This choice is justified by:

-

Theoretical Legitimacy: It aligns with the mathematical integrity of viewing

nullas the “Empty Set.” It rejects the premise thatnullitself is theoretically invalid and instead posits that safety arises from how it is handled. -

Simplicity and Directness: It avoids the potential structural complexity of nested

Optiontypes. A value is either present or it isnull, directly mirroring states like an empty spreadsheet cell. This often leads to simpler data structures and logic. -

Safety Through Discipline: Following the successful model of TypeScript,

nullis permissible, but its usage must be protected by safety mechanisms. The “safe mechanism” in this library is the strict discipline and convention imposed upon the user to always check fornullusing a helper function likeisNullbefore attempting to use a value from aTimelinethat might be absent.

This disciplined pattern serves as the necessary “safe operation” and “guard rail” in our framework. By adhering to this convention, the dangers historically associated with null are effectively mitigated within the context of using this library.

We position this approach as a theoretically valid path that consciously diverges from the mainstream HM/Option tradition to prioritize conceptual clarity and representational simplicity. The philosophy established in this chapter is foundational for the APIs we will introduce, such as combineLatestWith, and demonstrates how this disciplined approach to null leads to the construction of a clear and predictable reactive system。