Functor: Mapping between Functions

After exploring Monoids as our first algebraic structure, we now turn to another fundamental concept in functional programming: the Functor .

The term “Functor” originates from category theory , a fascinating branch of mathematics that deals with abstract structures and their relationships. While a complete treatment of category theory would be beyond the scope of this introductory book, we will cover it in detail in a companion volume dedicated to the mathematical foundations of functional programming.

Category theory is indeed a rich and profound field that deserves its own focused treatment. However, mixing its full theoretical depth with our practical introduction to functional programming could potentially overwhelm learners regarding both topics. For now, we’ll focus on just the aspects of Functors that are directly relevant to everyday functional programming.

Within the scope of functional programming, we’ve been dealing exclusively with functions and their theoretical foundation in set theory . Category theory’s notion of categories is highly abstract, but when we restrict ourselves to set theory (working in what mathematicians call the “category of sets” ), things become much more concrete and straightforward.

Functor in Functional Programming

Section titled “Functor in Functional Programming”Note that this title does not imply that the meaning or concept of Functor differs between functional programming and category theory. Rather, as mentioned in the opening note, we are simply focusing on Functors within the scope of set theory, which forms the foundation of functional programming, rather than dealing with the full breadth of category theory.

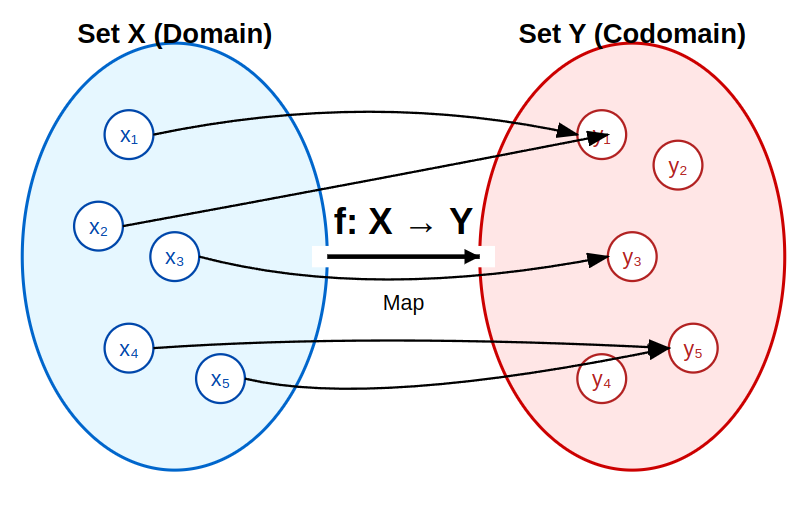

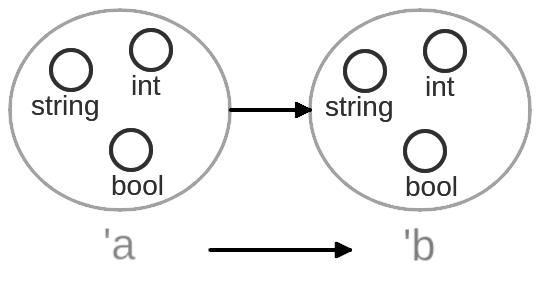

Let’s recall our discussion from “Set Theory and Types: A Deeper Look”. We saw this fundamental diagram of mapping:

This represents a general mapping where Set X (Domain) is mapped to Set Y (Codomain) by a function f.

Most importantly, we’re already very familiar with the idea that functions themselves are values in functional programming.

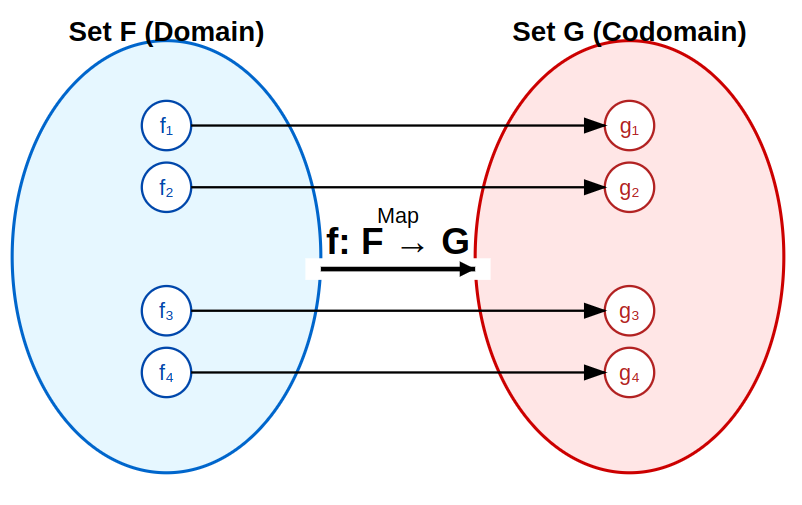

In this context, a Functor is essentially this same kind of mapping, but where both Set X and Set Y are sets of functions.

For clarity, let’s call these sets of functions Set F and Set G:

Here, we introduced the concept of a Functor using an analogy based on familiar ideas of mapping as shown in the diagram. We extended the idea of mapping values between sets to mapping functions between sets of functions to build an initial intuition.

It’s important to understand that this initial explanation was designed primarily to help grasp the core intuitive idea behind Functors – the concept of transforming content while preserving structure.

However, as our more detailed discussions will reveal later, this analogy alone is insufficient for a rigorous definition of a Functor. To define Functors precisely, we need to introduce the Functor Laws (Identity and Composition), which are specific rules that these operations must satisfy.

Please rest assured, we will delve into the strict definition of a Functor, detailing the Functor Laws and their significance, in a later chapter. Consider this initial introduction as a stepping stone towards that deeper and more formal understanding.

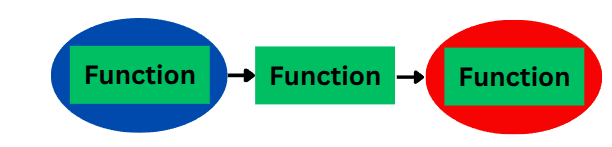

Basic Higher-Order Function (HOF) Pattern 3

Section titled “Basic Higher-Order Function (HOF) Pattern 3”This concept precisely corresponds to Basic Higher-Order Function (HOF) Pattern 3.

Function |> Function = Function

Takes and Returns a Function as input and also returns a function as output.

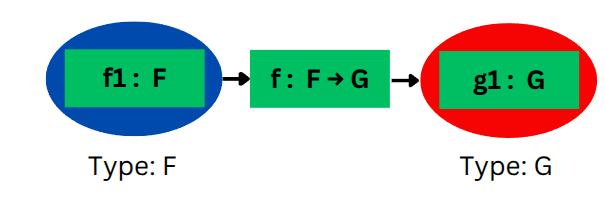

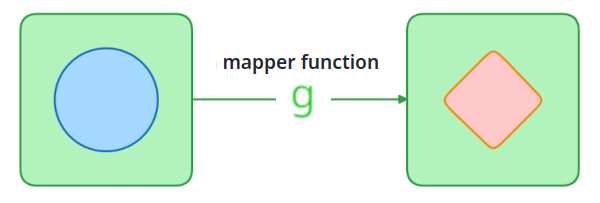

Mapper function of Container Type

Section titled “Mapper function of Container Type”Type expression 'a -> 'b using generic type parameters represents any possible function - it’s the most general form of function type that maps from any type 'a to any type 'b.

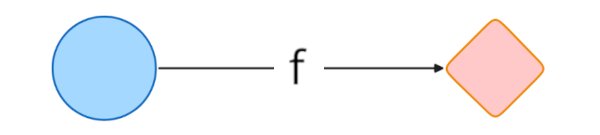

For visual clarity, we can represent these generic type parameters using shapes - a circle for any input type and a square for any output type:

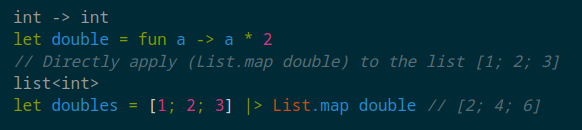

In this context, a typical scenario is when we already have a well-understood function and want to maintain its exact relationship when working with container types. For example, consider the simple double function that we know very well:

let double = fun a -> a * 2// Takes a number, returns twice that numberWhen working with a list container like [1; 2; 3], we often want to preserve this same doubling relationship. If double maps 1 to 2, we want a mapper function (= g) that can transform the entire list [1; 2; 3] to [2; 4; 6], maintaining the same doubling relationship for each element in the container.

With List as a container type, we can express List<'a> -> List<'b>.

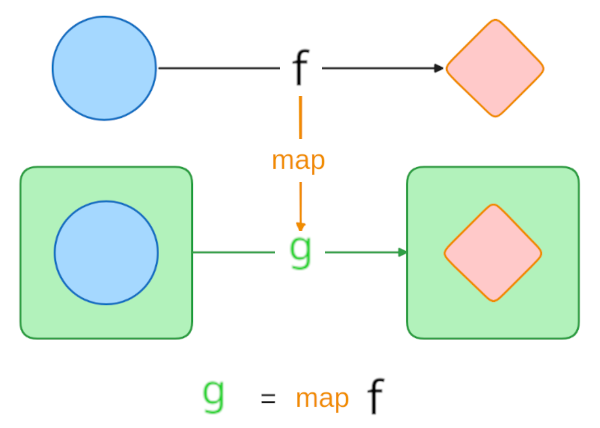

The map Function: A Bridge Between Worlds

Section titled “The map Function: A Bridge Between Worlds”To apply a regular function (like f: 'a -> 'b) to values “inside” a container type (e.g., to each element of a List<'a> to produce a List<'b>), we need a special higher-order function. This function is commonly called map (or sometimes fmap).

The map function itself is a HOF. Its role is to take two arguments:

- A function

fof type'a -> 'b. - A container

F<'a>(e.g., aList<'a>,Option<'a>).

And it returns a new container F<'b> of the same structure, but with the inner values transformed by f.

The type signature for map associated with a Functor F is typically:

map: ('a -> 'b) -> F<'a> -> F<'b>

Or, if we consider map as a function that first takes the function f and then returns a new function that operates on the container (aligning with HOF Pattern 3), its curried type signature would be:

map: ('a -> 'b) -> (F<'a> -> F<'b>)

This map function is the defining characteristic of a Functor. It provides the “bridge” that allows us to lift ordinary functions into the context of the container type.

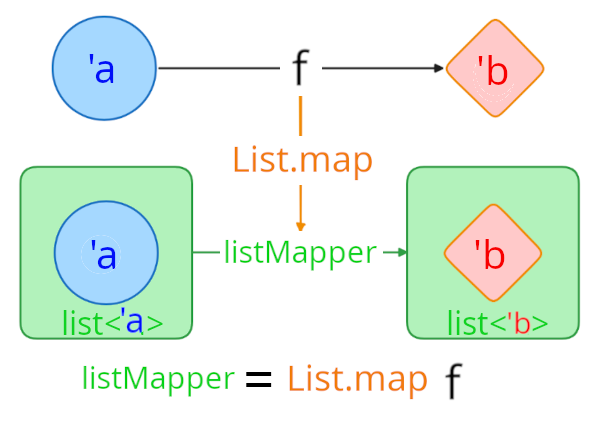

To obtain this mapper function g (that operates on the container, e.g., List<'a> -> List<'b>), what we need is this special map function that can transform our well-known function f (e.g., 'a -> 'b) into g:

(Here, map is the HOF that takes f and produces g)

As we confirmed in the first half of this chapter, this is precisely what a Functor is - a mapping between sets of functions that preserves their relationships. In other words, this map function that transforms our familiar function f into a container mapper function g is itself a Functor.

This map function is the key that bridges the world of simple functions with the world of container types, while maintaining the essential relationships we care about. And this is precisely what makes a Functor so powerful.

List.map: A Practical Example of Functor

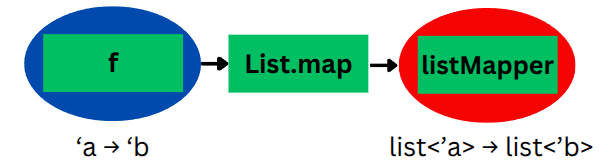

Section titled “List.map: A Practical Example of Functor”Let’s look at a concrete example using List.map, one of the most common implementations of Functor in functional programming:

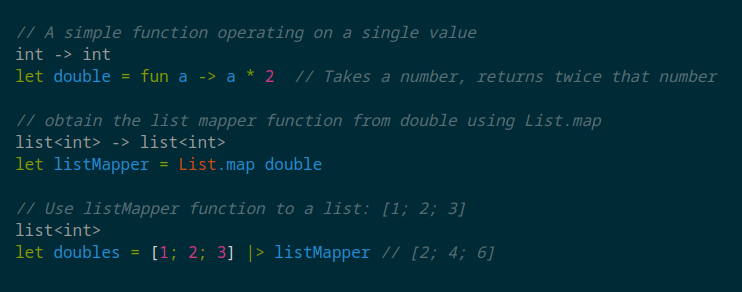

// A simple function operating on a single valuelet double = fun a -> a * 2 // Takes a number, returns twice that number

// obtain the list mapper function from double using List.maplet listMapper = List.map double

// Use listMapper function to a list: [1; 2; 3]let doubles = [1; 2; 3] |> listMapper // [2; 4; 6]

Here, the IDE’s type annotations reveal exactly how List.map as a Functor transforms our function types:

doublehas typeint -> int- a function that maps an integer to another integer- When we apply

List.maptodouble, we getlistMapperof typelist<int> -> list<int>- a function that maps a list of integers to another list of integers - The type transformation preserves the structure: what was

intbecomeslist<int>, but the fundamental mapping relationship is maintained

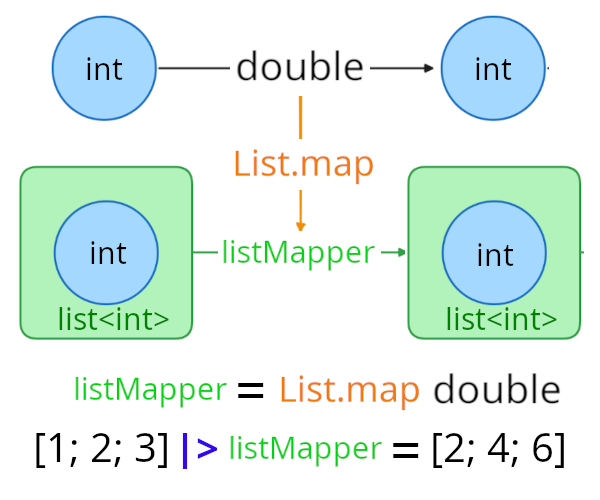

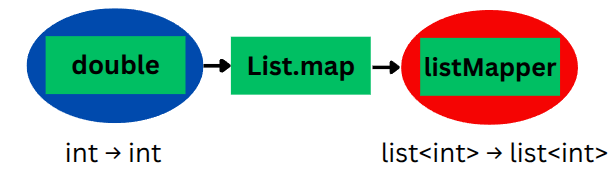

Here, List.map is actually transforming our double function into listMapper function:

This is exactly what our abstract definition was describing - List.map as a Functor lifts our simple double function into the world of containers while preserving its essential behavior of doubling each value.

Type of List Functor

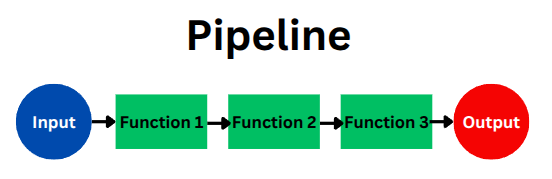

Section titled “Type of List Functor”Let’s see how our concrete example fits into the HOF pipeline pattern:

This is exactly our pipeline pattern - a function goes in, and a new function comes out. In this case, our double function of type int -> int goes into List.map and comes out as listMapper of type list<int> -> list<int>.

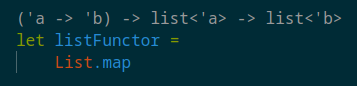

And here’s the beauty of F#‘s type system - while we’ve been working with a simple int -> int function, the IDE reveals that List.map’s actual implementation is much more general:

This type signature shows that List.map can work with any function from 'a to 'b, not just our specific int -> int example. It will always produce a function that operates on list<'a> and returns list<'b>, preserving the relationship between types.

We’ve seen how Functors, while originating from category theory, can be understood quite practically in functional programming as a way to transform functions while preserving their composability. Through the example of List.map, we’ve seen how this abstract concept translates into useful programming patterns.

Comparing the implementation of List Functor in F# and JavaScript/TypeScript highlights the differences in programming paradigms and type systems.

The implementation of List.map Functor is originally a two-step process:

// 1. Pass double to List.map to generate listMapper functionlet listMapper = List.map double

// 2. Apply the generated listMapper function to [1; 2; 3]let doubles = [1; 2; 3] |> listMapper // [2; 4; 6]In F#, this process can be written directly in one line using the pipeline operator:

let doubles = [1; 2; 3] |> List.map double // [2; 4; 6]Interestingly, this pipeline syntax leads to a visual structure that looks remarkably similar to what JavaScript programmers are familiar with. Let’s look at the JavaScript code:

const double = a => a * 2;const doubles = [1, 2, 3].map(double); // [2, 4, 6]Notice how similar these two lines appear? Both flow from left to right, both transform a list using a function named ‘map’. However, this superficial similarity actually highlights a fundamental difference between functional programming and object-oriented programming approaches.

In our functional approach with F#, as we’ve seen throughout this chapter, we use List.map as a Functor to create a listMapper function - this aligns perfectly with our pipeline principle of building transformations using functions as building blocks. The data and the functions that process it are kept separate, allowing for clear composition of transformations.

In contrast, the JavaScript OOP approach embeds the map method directly into Array objects. From a pipeline perspective, this means the transformation function (map) is embedded within the very data it’s supposed to transform. This breaks our straightforward pipeline model where data flows through independent transformation functions.

Consider our basic pipeline principle:

- Data flows through the pipeline

- Functions transform the data at each step

- Functions and data are separate entities

The OOP approach violates this clean separation by putting methods inside the data structures themselves. It’s as if we’re trying to build a pipeline, but the pipes come pre-built with certain transformations embedded in them. This makes it harder to think about and compose transformations independently of the data they operate on.

This fundamental difference in design philosophy - keeping functions and data separate (FP) versus embedding methods in objects (OOP) - becomes particularly apparent when we consider how these approaches scale to more complex transformations.

Moving to a different but related topic - the representation of types - we can see another significant difference between these languages when we look at TypeScript code:

Furthermore, the difference in type systems becomes more pronounced in TypeScript code:

const double = (a: number): number => a * 2;// Directly apply the map method to the array literal [1, 2, 3]// TypeScript infers the type of [1, 2, 3] as number[]// and the type of 'doubles' as number[] based on the return type of 'double'.// We add an explicit type annotation for clarity.const doubles: number[] = [1, 2, 3].map(double); // [2, 4, 6]TypeScript, a language that adds types to JavaScript, indeed has type inference capabilities, but often programmers need to explicitly write type annotations in the code (or with the help of AI). This enhances code readability but also increases code verbosity.

On the other hand, F#‘s type system is more sophisticated:

As shown in this image, in F#, there is no need to explicitly write type annotations. The compiler accurately infers the types and displays that information to the developer through the IDE. The type information that needs to be explicitly written in TypeScript is automatically provided in F#, while keeping the code clean. This is the benefit of the powerful type inference system characteristic of the ML family of languages.

Summary

Section titled “Summary”The key insights are:

- A Functor is a way to lift functions to work with containerized values

- It preserves the structure and composition of the original functions

- List is one of the most common and practical examples

This understanding of Functors sets us up for our next topic: Monads, which build upon these ideas to handle more complex computational contexts.