Beyond Simple Mapping: Preserving the Structure of Composition

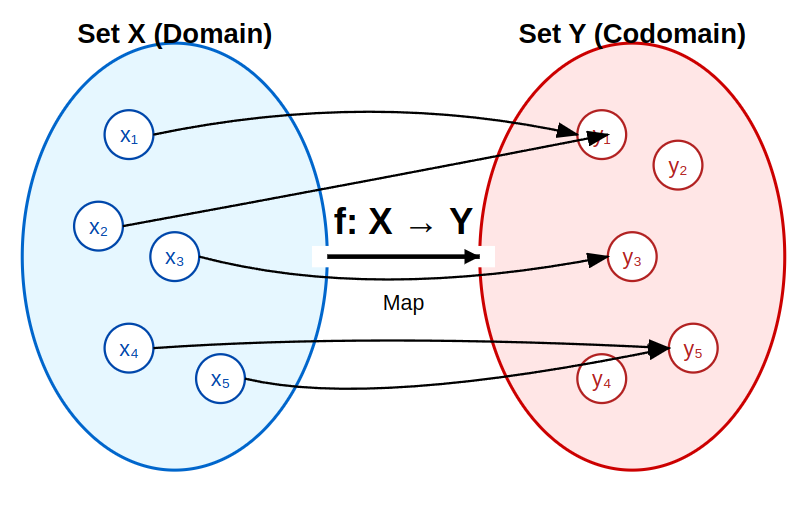

In our initial exploration of Functors (in Unit 2, Section 4), we used a helpful analogy to build intuition. We revisited the basic concept of mapping between sets:

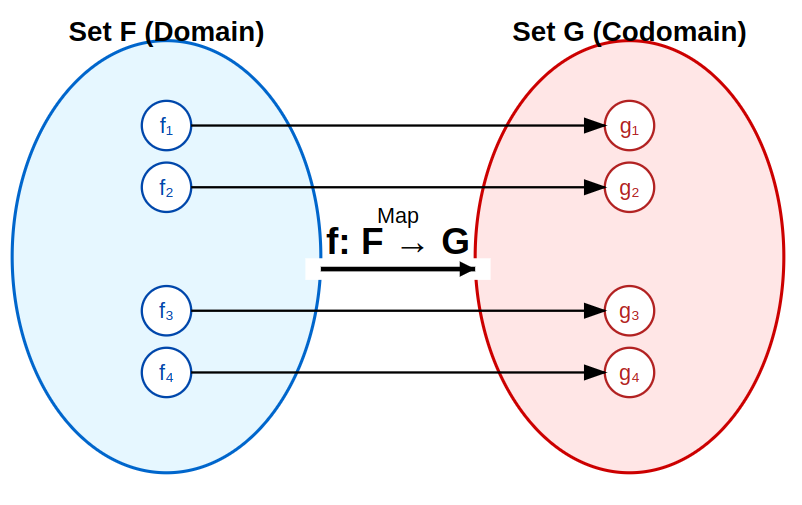

And extended this idea to mapping between sets of functions:

In this context, a Functor is essentially this same kind of mapping, but where both Set X and Set Y are sets of functions.

For clarity, let’s call these sets of functions Set F and Set G:

This analogy, comparing a Functor to a Higher-Order Function that transforms functions, serves as a useful starting point. However, as noted previously, this view is incomplete:

Here, we introduced the concept of a Functor using an analogy based on familiar ideas of mapping as shown in the diagram. We extended the idea of mapping values between sets to mapping functions between sets of functions to build an initial intuition.

It’s important to understand that this initial explanation was designed primarily to help grasp the core intuitive idea behind Functors – the concept of transforming content while preserving structure.

However, as our more detailed discussions will reveal later, this analogy alone is insufficient for a rigorous definition of a Functor. To define Functors precisely, we need to introduce the Functor Laws (Identity and Composition), which are specific rules that these operations must satisfy.

So, what exactly is missing from this initial analogy? Why is simply being a mapping between functions not enough? To understand the “More Than That” required for Functors and Monads, we need to look at the crucial concept of structure preservation, particularly concerning function composition. The key lies in understanding the robust structure already inherent in function composition itself.

The Foundation: Function Composition is a Natural Monoid

Section titled “The Foundation: Function Composition is a Natural Monoid”Let’s recall our discussion from Unit 2, Section 3 (“Function Composition: A Natural Monoid”). We established a fundamental and truly remarkable property: function composition forms a Monoid.

For functions that map a type back to itself (like int -> int or 'a -> 'a), the act of composing them using the >> operator exhibits:

- Associativity:

(f >> g) >> his equivalent tof >> (g >> h). The grouping doesn’t matter. - Identity Element: The

idfunction (fun x -> x) acts as an identity:id >> f = fandf >> id = f.

This inherent Monoid structure means function composition is naturally robust and predictable. Combining functions sequentially “just works” in a mathematically sound way, much like adding numbers or concatenating strings. This reliable structure is the bedrock upon which functional programming builds its pipelines.

The Structure Preservation Problem

Section titled “The Structure Preservation Problem”Now, let’s consider the world of containers and the functions that operate on them, like map (for Functors) and bind (for Monads). We need to examine composition in three distinct contexts:

- (Inner World) Composition of Regular Functions: As we just reaffirmed, functions operating on regular values inside containers (like

f: A -> Bandg: B -> C) can be composed (f >> g: A -> C), and this composition forms a Monoid (when types align appropriately, e.g.,A -> A). This is our baseline, well-behaved structure.

- (Outer World) Composition of Mapping Functions: The functions that

mapandbindproduce – the ones that operate on containers (likemap f: List<A> -> List<B>andmap g: List<B> -> List<C>) – can also be composed. We can certainly define(map f) >> (map g): List<A> -> List<C>. Function composition works here too, forming its own Monoid structure in the “outer” world of container transformations.

-

The Core Question: Does Lifting Preserve Structure? Here lies the crucial issue. We have a Monoid structure for composing regular functions (like

f >> gin world 1). We also have a Monoid structure for composing the container mapping functions (likemap f >> map gin world 2). The operationsmapandbindact as bridges, “lifting” functions from world 1 to world 2. The critical question is: Does this lifting operation preserve the Monoid structure?Specifically:

- Does mapping the identity function (

id) result in an identity mapping function for containers? (map id = id_container?) - Does mapping a composed function (

f >> g) yield the same result as composing the mapped functions (map f >> map g)? Ismap (f >> g)equivalent to(map f) >> (map g)?

This equivalence is not automatically guaranteed just because

mapis a higher-order function. It’s an additional property we might desire. - Does mapping the identity function (

The Requirement: Why Structure Preservation Matters

Section titled “The Requirement: Why Structure Preservation Matters”Why should we care if map or bind preserves the structure of composition and identity? Because requiring this preservation leads to more predictable, reliable, and composable abstractions.

If map (f >> g) is guaranteed to be the same as map f >> map g, it means we can reason about composing functions either before lifting them into the container world or after, and the result will be the same. This allows us to refactor code, optimize pipelines, and build complex transformations with confidence, knowing that the behavior remains consistent across these different levels of abstraction. Without this guarantee, the connection between the simple functions (f, g) and their containerized counterparts (map f, map g) becomes less predictable, making the abstractions less robust. We want our lifted functions to respect the fundamental algebraic structure of the functions they originate from.

The Origin: Category Theory and Monoids

Section titled “The Origin: Category Theory and Monoids”This idea of structure preservation is not arbitrary; it’s a cornerstone of Category Theory, the branch of mathematics from which Functors and Monads originate. Category Theory studies abstract structures consisting of objects and structure-preserving maps between them (called morphisms or arrows).

A fundamental requirement in Category Theory is that mappings between categories (which are called Functors) must preserve the essential structure of the source category, namely:

- They must map identity morphisms to identity morphisms.

- They must map the composition of morphisms to the composition of the mapped morphisms.

This focus on preserving composition and identity is deeply related to Monoids. As Saunders MacLane, one of the founders of Category Theory, noted in his seminal text “Categories for the Working Mathematician”:

(Source: Saunders MacLane, Categories for the Working Mathematician, 2nd ed., p. 7)

This highlights that the very foundation of Category Theory is built upon the Monoid concept (associative operation + identity). Therefore, it’s natural that key constructs derived from it, like Functors and Monads, are defined in a way that respects and preserves this fundamental monoidal structure inherent in composition.

Formalizing Preservation: The Laws

Section titled “Formalizing Preservation: The Laws”So, how do we mathematically enforce this requirement that map (for Functors) and bind (for Monads) preserve the structure of composition and identity? We do it through specific rules known as the Functor Laws and Monad Laws.

These laws, which we will detail in the following sections are not arbitrary constraints. They are the precise mathematical formalization of the structure preservation principle we’ve just discussed. They guarantee that these operations behave predictably and consistently with the underlying Monoid structure of function composition.

Essence and Intuition: Structure Preservation is Key

Section titled “Essence and Intuition: Structure Preservation is Key”Understanding Functors and Monads primarily as structure-preserving transformations provides a powerful intuition. They are more than just ways to apply functions to values inside containers; they are bridges between computational contexts that respect the fundamental algebraic rules of composition and identity – the rules embodied by the Monoid structure.

Thinking “Does this preserve the Monoid of composition?” is a more insightful way to approach Functors and Monads than just memorizing the specific laws. This perspective provides the conceptual foundation needed to truly understand why the laws exist and what guarantees they provide.

With this understanding of structure preservation as our stepping stone, we are now ready to examine the specific Functor Laws in detail.