Deconstructing HOF Types: From 'a -> 'b to Complex Signatures

In the previous chapter, we established that the generic function type 'a -> 'b is fundamental. It represents a function taking an input of some type 'a and returning an output of some type 'b, forming the very essence of functional transformation.

Now, let’s revisit the Higher-Order Function (HOF) patterns we encountered in Unit 1, Section 2 (“Higher-Order Functions (HOF)”). We will analyze their type signatures to see how they are logically and naturally constructed from this core 'a -> 'b concept. Understanding this will demystify seemingly complex HOF type signatures.

The Foundation: Visualizing 'a -> 'b

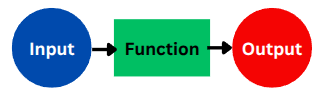

Section titled “The Foundation: Visualizing 'a -> 'b”Recall the general visual representation of a function from our initial discussion on HOFs:

This diagram perfectly illustrates the 'a -> 'b structure: an “Input” (type 'a) goes into a “Function” (the transformation logic), and an “Output” (type 'b) emerges. With HOFs, either the “Input” or “Output” (or both) can themselves be functions.

Analyzing HOF Pattern Types

Section titled “Analyzing HOF Pattern Types”Let’s break down the three HOF patterns and their corresponding generic type signatures.

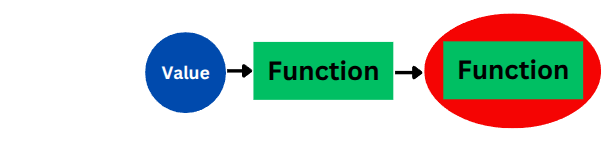

Pattern 1: HOF Returns a Function

Section titled “Pattern 1: HOF Returns a Function”Value |> HOF = Function

This pattern describes a HOF that:

-

Takes a regular “Value” as input. Let’s say this input value has type

'a. -

Returns a new “Function” as its output. Let’s say this new, returned function has the type

'b -> 'c(it takes a'band returns a'c).

Therefore, the HOF itself, which performs this transformation from an 'a to a function of type 'b -> 'c, has 'a -> ('b -> 'c)

In many functional programming languages, the -> operator in type signatures is right-associative.

This means that

'a -> ('b -> 'c)

is often written more concisely as:

'a -> 'b -> 'c

This notation signifies a function that takes an 'a and returns a function of type 'b -> 'c. The mechanics of how functions can accept arguments sequentially, leading to such type structures (often related to a concept called currying), will be explored in detail in Section 4.

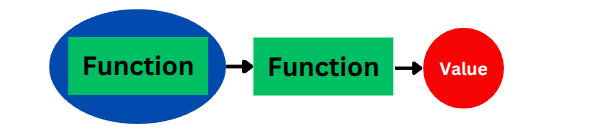

Pattern 2: HOF Takes a Function (and Returns a Value)

Section titled “Pattern 2: HOF Takes a Function (and Returns a Value)”Function |> HOF = Value

This pattern describes a HOF that:

-

Takes a “Function” as one of its inputs. Let’s say this input function has the type

'a -> 'b. -

May take other regular “Values” as input.

-

Returns a regular “Value” as its final output (not another function). Let this output value have type

'c.

The most general type signature for this pattern, where a HOF takes an input function and potentially other arguments to produce a final value, can be broadly represented as:

('a -> 'b) -> 'c

Here, 'c represents the final output value type.

Clarifying Type Signatures: Pattern 1 vs. Pattern 2 and the Role of Parentheses

Section titled “Clarifying Type Signatures: Pattern 1 vs. Pattern 2 and the Role of Parentheses”Let’s precisely compare the type structures of Pattern 1 and Pattern 2, paying close attention to how parentheses and the right-associativity of the -> type constructor shape their meaning.

1. Pattern 1: 'a -> ('b -> 'c) (Often written as 'a -> 'b -> 'c)

-

Core Structure: This type signature, fundamentally

'a -> ('b -> 'c), describes a function that:- Accepts a single argument of type

'a'. - Upon receiving this argument, it returns a new function. This returned function has the type

'b -> 'c', meaning it is ready to accept an argument of type'b'to then produce a value of type'c'.

- Accepts a single argument of type

-

Right-Associativity and Shorthand: In many functional languages, the

->type constructor is right-associative and often written as:'a -> 'b -> 'c

2. Pattern 2 (General Form): ('a -> 'b) -> 'c

- Core Structure: This type signature describes a function whose very first argument is, itself, a function.

- It expects a function of type

'a -> 'b'as its initial input. - After receiving this function (and potentially other subsequent arguments), it ultimately returns a single value of type

'c'.

- It expects a function of type

- Essential Parentheses: The parentheses around

('a -> 'b)are structurally critical. They explicitly group'a -> 'bas the type of the first parameter. Unlike the parentheses in Pattern 1’s full form'a -> ('b -> 'c)(which can be omitted due to right-associativity), these cannot be removed without fundamentally altering the function’s meaning.

These two types ('a -> 'b -> 'c and ('a -> 'b) -> 'c) describe functions that expect fundamentally different kinds of inputs at their first step and thus behave very differently. The type system enforces this distinction rigorously.

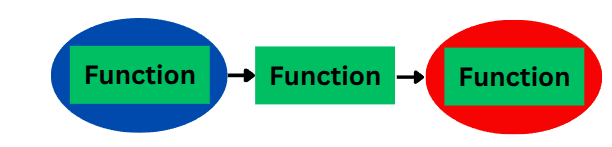

Pattern 3: HOF Takes a Function and Returns a Function

Section titled “Pattern 3: HOF Takes a Function and Returns a Function”Function |> HOF = Function

This pattern describes a HOF that:

-

Takes a “Function” as input. Let’s say this input function has the type

'a -> 'b. -

Returns a new “Function” as its output. Let’s say this new, returned function has the type

'c -> 'd.

Therefore, the HOF itself has a generic type signature like:

('a -> 'b) -> ('c -> 'd)

Regarding the parentheses:

-

Similar to Pattern 1, the output part of this HOF (which is the function

'c -> 'd) means this HOF’s type can also be seen as('a -> 'b) -> 'c -> 'ddue to the right-associativity of the->operator. This signifies that after taking the initial function('a -> 'b), the HOF returns a new function of type'c -> 'd. -

However, just like in Pattern 2, the parentheses around the input function type

('a -> 'b)are structurally essential. They indicate that the HOF’s first argument is itself a function of type'a -> 'b. These parentheses cannot be omitted or re-associated without changing the meaning (i.e., it’s not'a -> 'b -> 'c -> 'd', which would imply a different sequence of non-function arguments initially).

So, the type ('a -> 'b) -> 'c -> 'd correctly represents this HOF that:

-

takes a function

('a -> 'b) -

returns a new function

'c -> 'd.

Conclusion: HOF Types as Natural Extensions

Section titled “Conclusion: HOF Types as Natural Extensions”As we’ve seen, the type signatures of these fundamental HOF patterns are not arbitrary. They are logical and natural constructions built upon the basic 'a -> 'b functional type.

- When a HOF returns a function, the return part of its type signature becomes a function type itself (e.g.,

... -> ('x -> 'y)). - When a HOF takes a function as input, one of its parameters in the type signature is a function type (e.g.,

('x -> 'y) -> ...).

Recognizing how the 'a -> 'b structure can be nested and combined to describe HOFs is crucial. It reinforces the concept of functions as first-class citizens whose types can be composed and reasoned about, just like any other data type. This understanding will be invaluable as we encounter more sophisticated HOFs and functional patterns, such as Functors and Monads (which often involve HOFs with types like (a -> b) -> F a -> F b or (a -> M b) -> M a -> M b), in later units.