Chapter 3: bind — The Dynamic Dependency Graph

In Chapters 1 and 2, we saw how .map() and .link() build static dependencies that, once defined, do not change.

However, .map() can only transform values; it cannot switch the Timeline itself. The challenge of dynamically and safely switching the dependency structure itself (i.e., while cleaning up old dependencies) is solved by .bind().

.bind() — The HOF for Switching Dependencies

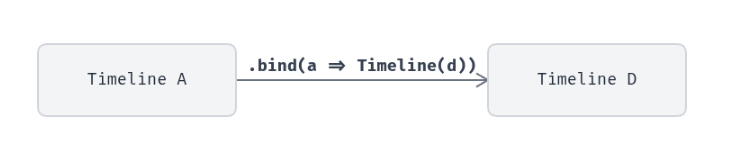

Section titled “.bind() — The HOF for Switching Dependencies”The essence of .bind() is not merely to transform a value, like .map(), but to accept a function that, based on the value of the source Timeline, returns the next Timeline to connect to.

This allows us to build dynamic systems where the wiring of the dependency graph changes over time.

API Definition

Section titled “API Definition”F#: bind: ('a -> Timeline<'b>) -> Timeline<'a> -> Timeline<'b>

Section titled “F#: bind: ('a -> Timeline<'b>) -> Timeline<'a> -> Timeline<'b>”TS: .bind<B>(monadf: (value: A) => Timeline<B>): Timeline<B>

Section titled “TS: .bind<B>(monadf: (value: A) => Timeline<B>): Timeline<B>”The crucial difference from .map() is that the function it takes (monadf) accepts a value A and returns a new Timeline<B>.

What is the use of bind or the Monad algebraic structure in a FRP library like Timeline?

Section titled “What is the use of bind or the Monad algebraic structure in a FRP library like Timeline?”Throughout this book, we have investigated the abstract concept of the Monad algebraic structure and its concrete function, bind. But what is the use of this Monad in FRP?

In reality, most programmers do not have an answer to this mystery. And perhaps even the developers of existing FRP libraries and participants in their ecosystems do not. It is observed that they likely do not have a clear answer.

Therefore, I would like to present a clear answer here and now.

The Diamond Problem in FRP Libraries—Atomic Update

Section titled “The Diamond Problem in FRP Libraries—Atomic Update”1. Definition of the Diamond Problem

Section titled “1. Definition of the Diamond Problem”The diamond problem in Functional Reactive Programming (FRP) refers to issues of glitches and inefficiency that arise when a dependency graph forms a diamond shape. Specifically, it occurs when a timeline D depends on two other timelines, B and C, both of which depend on a common source, A.

A / \ B C \ / DIn this structure, when the value of A is updated, the change propagates to both B and C, and subsequently, the updates from B and C propagate to D.

The Problem:

Section titled “The Problem:”- When A is updated, B and C are updated.

- However, if the update order of B and C is indeterminate, D may be updated twice at different times.

- D might be calculated with a temporarily inconsistent state (a glitch).

Concrete Example:

Section titled “Concrete Example:”Consider the case where the value of A changes from 5 to 10.

JavaScript

let A = 10;let B = A + 1; // Expected: 11let C = A * 2; // Expected: 20let D = B + C; // Expected: 31However, depending on the propagation order of updates, a glitch can occur.

-

If

Bis updated first,Dwill be calculated using the new value ofB(11) and the old value ofC(10).D = 11 + 10 = 21(Glitch) -

Afterward,

Cis updated, andDis recalculated using the new value ofB(11) and the new value ofC(20).D = 11 + 20 = 31(Final correct value)

This intermediate state (D=21) can cause unintended side effects (e.g., temporary UI flickering) and can be a source of serious bugs.

2. The Approach of Many Existing FRP Libraries

Section titled “2. The Approach of Many Existing FRP Libraries”To solve this deep-rooted problem, many existing FRP libraries (e.g., RxJS, Bacon.js, MobX) implement highly complex internal mechanisms. They primarily adopt an approach of not propagating updates synchronously and immediately, but rather queuing them and executing them in a controlled manner.

-

Topological Sort for Update Order Control: They analyze the dependency graph and reorder the execution of calculations to ensure updates are performed in the correct order:

A→B,A→C, then (B,C)→D. -

Bulk Updates via Transactions: All changes originating from an update to

A(i.e., updates toBandC) are grouped into a single “transaction.” Only after this transaction is complete (i.e., bothBandCare updated) is the calculation forDperformed, and only once. -

Consistency Checks with Timestamps: A timestamp is attached to each update. When calculating

D, the system checks that its dependencies (B,C) have updates with the same timestamp (i.e., originating from the same event) before performing the calculation.

These techniques are effective, but they complicate the library’s internal implementation and can lead to behavior that is opaque to the developer. This is also described as achieving atomic updates.

3. The Timeline Library’s Approach: “It’s Wrong for the Diamond Problem to Occur in the First Place”

Section titled “3. The Timeline Library’s Approach: “It’s Wrong for the Diamond Problem to Occur in the First Place””The Timeline library, rather than relying on such low-level mechanisms, cuts this problem off at its root through a higher level of abstraction. Its philosophy is the highly refined idea that “a design that allows the diamond problem to occur is itself flawed, and a better design should be chosen.”

Conceptual Purity: Expressing the Essence of “Defining D from A”

Section titled “Conceptual Purity: Expressing the Essence of “Defining D from A””The ultimate solution presented by this library is to use .bind (a monadic composition).

TypeScript

const D = A.bind(a => { const b = a * 2; const c = a + 10; return Timeline(b + c);});The reason this approach is superior to other libraries or workaround-style techniques lies in its conceptual purity. The essential dependency in the diamond problem is the fact that “the value of D is ultimately determined solely by the value of A.” B and C are merely intermediate values in that calculation process.

This code using bind expresses that essence in a remarkably straightforward way. For each value a of A, it defines a single, pure relationship that returns a Timeline containing the new state of D. This embodies the very philosophy of the library, elevating the perspective from an imperative world, often fraught with side effects, to a declarative world of data flow.

A single bind naturally forms a Monad structure that performs atomic updates. No complex underlying mechanisms are needed.

4. A Simple and Refined Solution Unmatched by Other Libraries

Section titled “4. A Simple and Refined Solution Unmatched by Other Libraries”The benefits of this bind approach are numerous.

1. Structural Elimination of Glitches

Section titled “1. Structural Elimination of Glitches”As a common approach, trying to define B and C separately with .map and then combining them to create D gives rise to the “problematic structure” of a diamond. However, by using bind, the dependency graph changes fundamentally.

There are no longer intermediate timelineB or timelineC, and the diamond structure itself is never formed. Therefore, problems like glitches and multiple updates cannot structurally occur. This is a solution on a different level: not fixing a problem after it occurs, but choosing a superior design where the problem does not arise.

2. Execution Efficiency

Section titled “2. Execution Efficiency”In this structure, every time A is updated, the function passed to bind is executed only once, and D is calculated only once. This is highly efficient.

3. Complete Elimination of Transactional Processing

Section titled “3. Complete Elimination of Transactional Processing”Even more importantly, the **complex

2. Execution Efficiency

Section titled “2. Execution Efficiency”In this structure, every time A is updated, the function passed to bind is executed only once, and D is calculated only once. This is highly efficient.

3. Complete Elimination of Transactional Processing

Section titled “3. Complete Elimination of Transactional Processing”Even more importantly, the complex, low-level processing such as transaction handling and scheduling, which other libraries perform under the hood to avoid glitches, becomes entirely unnecessary. By using a high-level abstraction (the Monad), this library achieves further execution efficiency and simplicity, eliminating the need for such wasteful processing.

4. Readability

Section titled “4. Readability”The logic for calculating the value of D from the value of A (the calculation of b and c, and their addition) is all contained within the bind callback. This dramatically improves code readability and makes the logic easier to maintain.

5. Conclusion: “A Design Where Problems Don’t Occur” through Monads

Section titled “5. Conclusion: “A Design Where Problems Don’t Occur” through Monads”Many other solutions are all “post-problem-fixes.” They are merely symptomatic treatments that attempt to hide the glitches that have occurred with a complex mechanism called a transaction.

However, bind enables “a design where problems don’t occur.” This is the very beauty of functional programming.

.bind is backed by the mathematical laws of Monad, and its behavior is completely predictable. With the powerful abstraction of the Monad, developers can completely control side effects (in this case, the unintended propagation of intermediate states) and safely describe only the essential computation.

The Timeline library, being faithful to theory, naturally provides not only .map but also .bind. This was not intentionally designed with the thought, “this can solve the diamond problem.” The Monad algebraic structure is there from the beginning.

This fundamentally theoretical library design is precisely the driving force that naturally provides developers with this “structurally elegant problem-solving,” and this is the proof of the design philosophy that sets this library apart from other FRP libraries.

The Natural Question of Performance

Section titled “The Natural Question of Performance”However, the fact that the function passed to .bind creates a new innerTimeline with every update of the source Timeline raises a natural concern for experienced developers: “Doesn’t this constantly create unnecessary objects, becoming a direct cause of performance degradation?” This question is valid and is a crucial point in understanding how the powerful concept of bind is made practical.

The Answer: A Design for Safely Realizing Dynamic Graphs

Section titled “The Answer: A Design for Safely Realizing Dynamic Graphs”In conclusion, there is no need to worry. The Timeline library is designed to execute the dynamic graph structure switching brought about by bind safely and efficiently. The core of this is that the framework completely and automatically disposes of any innerTimeline that has served its role, without any leaks. This is an extremely important implementation feature of this library that allows the powerful concept of bind to be utilized without the fear of resource leaks.

This mechanism for safely managing the dynamic graph structure is realized by the Timeline library’s heart, DependencyCore, and a concept called Illusion. Let’s take a closer look at this technical foundation next.

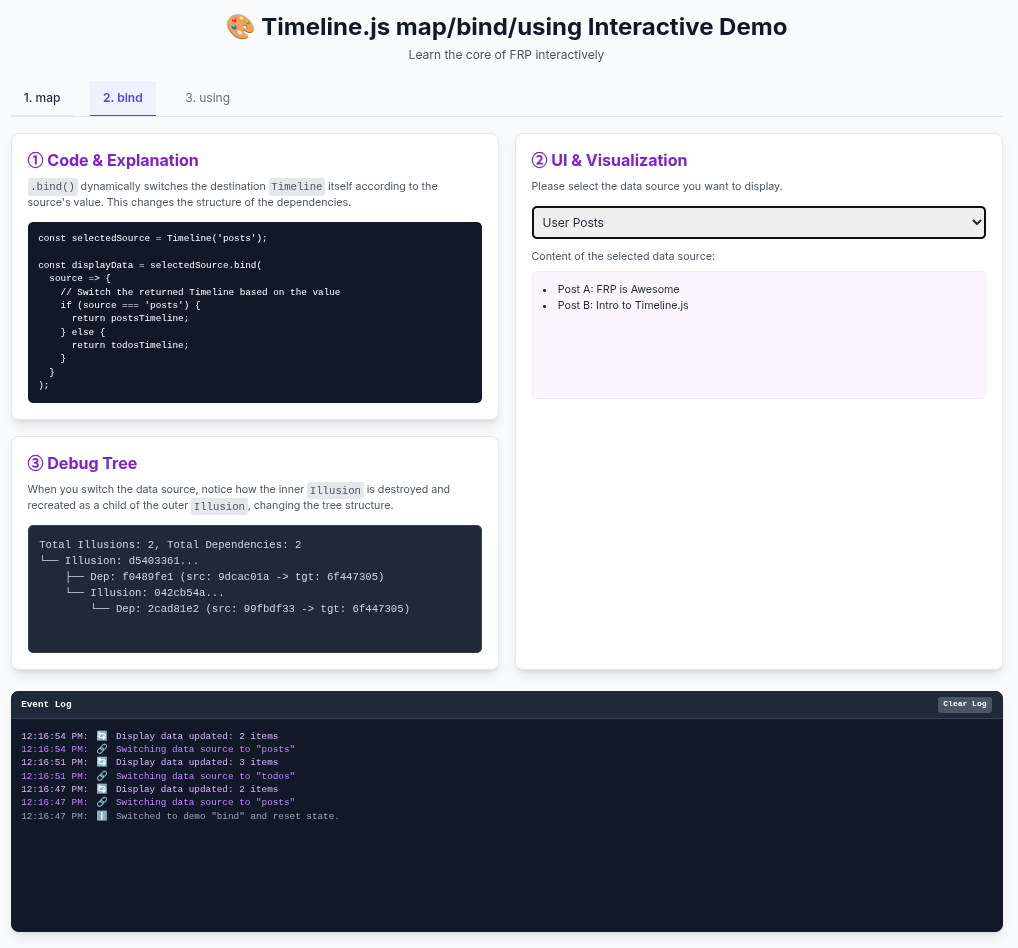

DependencyCore

Section titled “DependencyCore”How is this dynamic switching of dependencies achieved? The answer lies in the heart of the Timeline library: DependencyCore.

DependencyCore is an invisible central management system that records and manages the dependencies between all Timelines existing in the application. While .map() and .link() register static dependencies, .bind() utilizes this DependencyCore in a more advanced way.

Illusion — The Time-Evolving Dependency Graph

Section titled “Illusion — The Time-Evolving Dependency Graph”The dynamic switching of dependencies brought about by .bind() is a manifestation of a deeper, more powerful concept in the library’s design. To understand it, let’s first organize the different levels of “mutability” in map and bind.

-

Level 1 Mutability (The world of

map/link): In a static dependency, theTimelineobject itself is an immutable entity. The only thing that is “mutable” is the internal value_last, which is updated as theNowviewpoint moves. This can be called the minimal unit of illusion, the “current value” in the block universe. -

Level 2 Mutability (The world of

bind): When.bind()is introduced, this concept of mutability is extended. It’s no longer just the_lastvalue that gets replaced. TheinnerTimelineobject returned by.bind()is swapped out entirely according to the source’s value. This means that theTimelineitself, which defines the “truth” of a given moment, becomes a temporary, replaceable entity.

This “structural” level of mutability is the essence of the Illusion concept.

Conceptually, the resulting Timeline object from a bind call (e.g., currentUserPostsTimeline) is an immutable entity created only once.

However, for the exact same reason that our viewpoint, Now, is a mutable cursor moving along the timeline, the innerTimeline that is always synchronized with that cursor (e.g., the posts Timeline for "user123" or the posts Timeline for "user456") must also be mutable.

The fundamental reason the innerTimeline must be “destroyed” is that the dependency graph itself evolves over time in sync with the movement of the Now cursor, and the structure of the graph is different at each time coordinate.

This “state of the time-evolving dependency graph at a particular moment” is precisely what Illusion is. And the task of synchronizing the movement of the Now cursor with the rewriting of this Illusion (destroying the old and creating the new) is managed imperatively and collectively by DependencyCore.

In other words, Illusion is a concept that extends the “value-level mutability” of _last to the “structure-level mutability” of innerTimeline. And as we introduce .using() in subsequent chapters, this concept of mutability will be further extended to the “lifecycle of external resources.”

Application Case: Building Dynamic UIs

Section titled “Application Case: Building Dynamic UIs”So far, we have looked at the essential power of bind (building dynamic dependency graphs) and the library’s implementation that safely supports it (automatic resource management by DependencyCore and Illusion). So, what value is created in actual application development when this theory and implementation technology are combined? Let’s look at a scenario that frequently occurs in modern UI development: “dynamically switching the component to be displayed according to the user’s selection.”

In modern applications, the need to dynamically switch the dependency relationship itself arises frequently. For example, consider a case in a social media application where you switch the user’s timeline to be displayed.

// Alice's timelineconst alicesPosts = Timeline(["Alice's post 1", "Alice's post 2"]);

// Bob's timelineconst bobsPosts = Timeline(["Bob's post 1", "Bob's post 2"]);

// Currently selected user IDconst selectedUserId = Timeline("alice");

// Here, we want to switch between alicesPosts and bobsPosts depending on the value of selectedUserId// But this cannot be achieved with map...// const currentUserPosts = selectedUserId.map(id => {// if (id === "alice") return alicesPosts; // This returns a Timeline// else return bobsPosts;// });Practical Example: Dynamic Switching of a Social Media Timeline

Section titled “Practical Example: Dynamic Switching of a Social Media Timeline”Let’s implement the previous social media example using .bind().

const usersData = { "user123": { name: "Alice", posts: Timeline(["post1", "post2"]) }, "user456": { name: "Bob", posts: Timeline(["post3", "post4"]) }};

const selectedUserIdTimeline = Timeline<keyof typeof usersData>("user123");

// Depending on the selected user ID, switch the connection to that user's posts Timelineconst currentUserPostsTimeline = selectedUserIdTimeline.bind( userId => usersData[userId].posts);

console.log("Initial user posts:", currentUserPostsTimeline.at(Now));// > Initial user posts: ["post1", "post2"]

// Switch the user selectionselectedUserIdTimeline.define(Now, "user456");

console.log("Switched user posts:", currentUserPostsTimeline.at(Now));// > Switched user posts: ["post3", "post4"]This code example brilliantly demonstrates two aspects of bind.

First, the theoretical aspect: it describes the complex requirement of dynamically switching the UI state in a highly declarative way.

Second, the implementation aspect: behind the scenes, DependencyCore reliably disposes of the old innerTimeline through the Illusion mechanism, so the developer does not need to be conscious of resource management.

Thus, bind shows its true value only when a powerful theory and a robust implementation that supports it are combined.

Canvas Demo

Section titled “Canvas Demo”